The “Add More” Trap

When was the last time you solved a problem by removing something? A gap appears. Your instinct? Add more—new workflows, another hire, a new committee. Addition feels productive. Subtraction rarely even occurs to us.

This instinct isn’t just habit; it’s wired into us. Psychologists call it additive bias: our tendency to solve problems by adding elements, rather than taking them away. This bias drives our desire to say ‘yes’; which in turn leads to endless obligations — all noise and no signal.

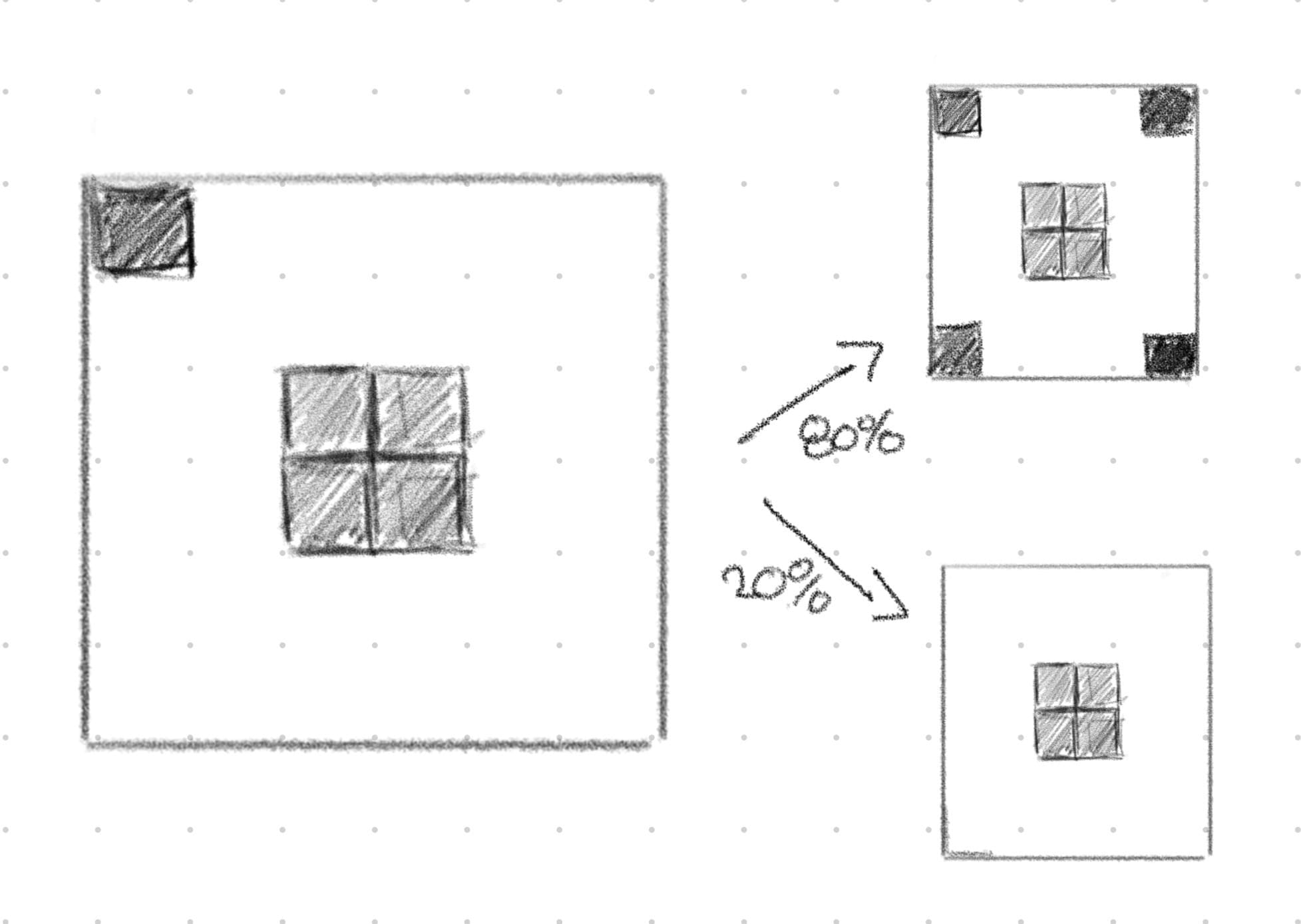

Imagine you are presented with a standard HB2 pencil (the best writing tool) and the following pencilled in grid of squares. You are asked to make the image symmetrical. What do you do? If you are like 80% of the individuals referenced in this study, you would add scribbles in 3 new squares even though erasing the square in the top left quadrant would be an adequate solution.

So why does this bias exist?

Research points to several causes, but two stand out. First: additive solutions are often easier to process cognitively. Take this common example—an initiative is launching inside a large, complex organization (sound familiar?). A clear decision-making structure is needed. The default move? Spin up a new multidisciplinary steering committee to provide centralized guidance. It sounds reasonable. But fast forward a few meetings, and the committee stalls. Despite having the right people in the room, it lacks the authority to make actual decisions.

Why? Because creating something new feels faster and cleaner than doing the harder work: mapping existing decision-making structures, understanding their gaps, and seeing if the problem can be solved through what’s already there.

The “Add More Trap” often pushes decisions upward, defaulting to committees packed with senior leaders. This may solve the authority gap—but at a cost. These leaders are rarely close enough to the work to make informed decisions across every initiative they're asked to weigh in on. The result? Bottlenecks and bloated governance.

Secondly the numerical concepts of ‘more’ and ‘higher’ are often cognitively correlated with the concepts of ‘positive’ and ‘better’. Bigger numbers, higher scores. At work, hitting more targets is rewarded. Performance reviews are a scoreboard — projects launched, goals smashed, milestones stacked up. But here’s the problem: no one notices what you didn’t do. The meeting that is killed; the extra hire that isn’t made; the convoluted idea that was dropped . Those don’t show up in the metrics. And Nobody measures the goals you never set. And if it’s not measured, it’s not rewarded.

So how do we combat this?

First we need to introduce circuit breakers that interrupt this natural bias towards “Add More”. At the start of problem-solving, ask yourself and the team: What could we remove? Make it a genuine first step, not an afterthought. Make no mistake this path of inquiry takes more time and effort.

Secondly make subtractions visible. John Doerr’s Measure What Matters makes a strong case for the power of OKRs (Objective and Key Results) — what you measure drives what you achieve. If you want subtraction to stick, you have to drag it into the light. That means counting it, naming it, and talking about it like it’s a win. The trick is to make removal as visible and rewarding as addition.

Objective: Strengthen clarity and reduce noise in decision-making within my team.

KR1: Remove at least 5 outdated policies from the internal knowledge base.

KR2: Shorten standard project status reports from 3 pages to 1 page.

KR3: Retire 1 standing cross-functional meeting that no longer aligns with strategy.

Before rolling out the next big idea, let’s pause. Look around. What’s clogging the system? What’s eating attention, budget, or patience without delivering real value? The easiest way to make space for something new is to stop doing something old. Subtraction isn’t 'cool'. It rarely makes the all-hands slide deck (except during massive budget cuts - and even then we try to sugar coat it); but it’s often the difference between change that sticks and change that just adds more noise. Before you add, consider what you can remove. Always.